Jane Abernethy at Helm of Humanscale Sustainability is Transforming Furniture Industry One Step at a Time

Highlights the importance of eco-friendly and circularity in design

Humanscale is a leading furniture brand that has been manufacturing high-performance ergonomic products to improve work and health. Founded in 1983 by Bob King, Humanscale, while always adhering to the principles of function, simplicity, and longevity, changed design practices to sustainability way back in 2014. Marking a decade of research and development of exceptionally ergonomic furniture with sustainability hand in hand, we get into a conversation with Humanscale’s Chief Sustainability Officer, Jane Abernethy.

In this insightful conversation, Jane Abernethy shares her journey as an industrial designer to currently heading a global initiative of eco-friendly and circular design at one of the leading furniture companies, upcoming projects, challenges, and how sustainability can bring about a positive change in the industry. A force of determination and resilience, Jane Abernethy believes there’s nothing as a failed project, just trials and errors until you get it right. Read the detailed account of this interaction.

Image: Humanscale

Planet Custodian (PC): Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to be a part of Humanscale.

Jane Abernethy (JA): I was an industrial designer for quite a few years. My last design job was at the in-house design studio at Humanscale.

I was always very passionate about making design choices that would be with the planet in mind and their impacts as well. So when I was designing at Humanscale, I had a lot of conversations and was quite vocal about that. Then I was eventually asked to lead a sustainability project, which grew into the department and now I run sustainability exclusively at Humanscale.

PC: What does being the Chief Sustainability Officer entail?

JA: I’m the Chief Sustainability Officer. There are a lot of different aspects to it, every day is quite different. I have a team as well, so we all work with our new product development, making sure that every new product meets our standards.

This also includes working with our operations teams and our supply chains to make sure that our producing and manufacturing really align with our values. Then, we work with our marketing and communications teams to ensure that all of the claims that we make and all of the things that we say lineup with the details of our final products.

I guess the last part is getting all of these things audited; third-party verified and making sure that the statements that we make can stand up.

PC: What is the ultimate sustainability goal for Humanscale that you have in mind?

JA: We have goals every year and we break them into different impact categories. But one of the main things that we’re focusing on next is circularity and we’ll see a lot more activity in that. It’s a very complex topic, a very simple idea to start with. Just the idea of reusing things sounds so simple and easy, but the reason why it’s not happening is because to make it happen in practice, there are a lot of details to work through.

Both culturally and people, attitudes and mind-shifting, getting people to think about things differently. Then there are a lot of logistical, and regulatory challenges to have material continue to cycle through and not be a linear economy, not support a linear economy, but start to transition to a circular economy.

Image: Humanscale

PC: How has your career path as an industrial designer prepared you for the current role?

JA: It might seem like I’m doing very different things, but in fact, a lot of the thinking is very similar. In industrial design – I think this is sometimes summarized as design thinking – it’s focused on understanding the fundamental challenge or the fundamental problem and then addressing that. Sometimes the most obvious solutions are not the final answer when you understand what you’re going for.

For example, nobody wants a toaster; people want to have toast. If you could get the toast without the toaster, nobody would be buying them, right? So that’s kind of the idea that if you understand what you’re going for is toast, then you don’t design a toaster the same way you might have many other ideas of what it could be. That is the solution to that problem.

I think that years of practice and really understanding the essence of what’s needed and then thinking of lots of different creative ways to meet that challenge, executing, and having the tenacity to execute on those ideas came from design and is. In some ways, I feel like I’m still designing, but not physical objects anymore.

PC: How and when did the sustainability journey for Humanscale kickoff? What was that spark that led to designing and creating sustainable objects?

JA: I get this question on myself as well as for Humanscale. Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint an exact moment when things would have changed. I will say that our CEO and founder has been passionate about the outdoors and wildlife for his whole life. He often goes on vacation in the wilderness and he’s talked about spending a lot of time in the woods and exploring as a young person.

We didn’t, as a company, have a cohesive centralized person leading this charge. So different departments approached it differently. I think until I took that position, leading a project in sustainability, and then grew that to leading a department.

I would say that it was an alignment of different interests at the time for the values of the company and the values of what I was interested in really wanting to push sustainability forward. It wasn’t about continuing to be sustainable in the basic understanding, but fundamentally understanding what we could do to move the needle. When I started asking questions, pushing thought what can we do to not just be better than average or better than we otherwise could be?

Where do we want to end up? We had around a year, year, and a quarter’s worth of conversations to find out what does it mean for us. Doing less harm wasn’t good enough. There are a lot of companies saying they’re going to reduce harm by a certain percentage at some point in the future, right?

So our thought was continuing to reduce harm is better than not doing anything, but it’s still not going to lead us to the world we want to live in. We want to see if it’s possible to manufacture, be a for-profit company, and leave the world better off because we’re here and I think we took that goal on in January or early of the year in 2014. It was a solidifying thought process and had a lot of momentum beforehand, but it solidified in January 2014.

Image: Humanscale

PC: People often think that sustainability is inversely related profit as opposed to fast fashion. How can you inspire others and your company to commit to sustainability and also the consumer to buy those things?

JA: I think they’re very connected. It might be often the point of view when you’re thinking of an individual purchase or a particular quarter. But when you zoom out, you realize that in the long run, the cost of not being sustainable becomes very expensive to the business.

I think of a company like Coca-Cola; they’ve got a lot of water conservation projects, but of course, it makes perfect business sense because if there’s not abundant water available, it’s challenging for them to make their product. If we realize that for all of us as companies, it’s the fewer resources that we leave available, the harder we make it for ourselves in the long-term in the future.

Decades ago, we had the luxury to say that at some point in the future, this is going to become challenging; but we’re now at the point where it is challenging. So, now it’s become clear that if we are not looking at sustainability and the risks, we’re going to pay for it with the business risks.

It’s like reusing material, which is much more efficient than extracting and processing new material, so sometimes it can be quite aligned in the very small, short-term benefits, like the energy bills going down. Shipping more efficiently is aligned with the financial bottom line.

But then you zoom out just a little bit and you realize that because they’re so interconnected, it’s whether we’re sustainable or not is going to affect business. It’s starting to affect businesses regularly now.

PC: How many products have been part of the company’s sustainable journey and what sort of innovative materials have you come up with so far?

JA: Usually my approach is to prove the concept and then try to scale up and eventually try to make it 100 percent but we’re not where we’re working towards these things. For example, our products that are certified climate positive – we have 29 of them now – and last year that represented over 70 percent of the product that we sold.

So it’s not like 29 out of 10,000. It’s a significant majority and closing in on more and more. We are very transparent about the material ingredients that make up our products. We transparently share what’s in them. And we’ve done that. Like last year, 83 percent of the products that we sold had materials labels to say exactly what are all the ingredients going into the products.

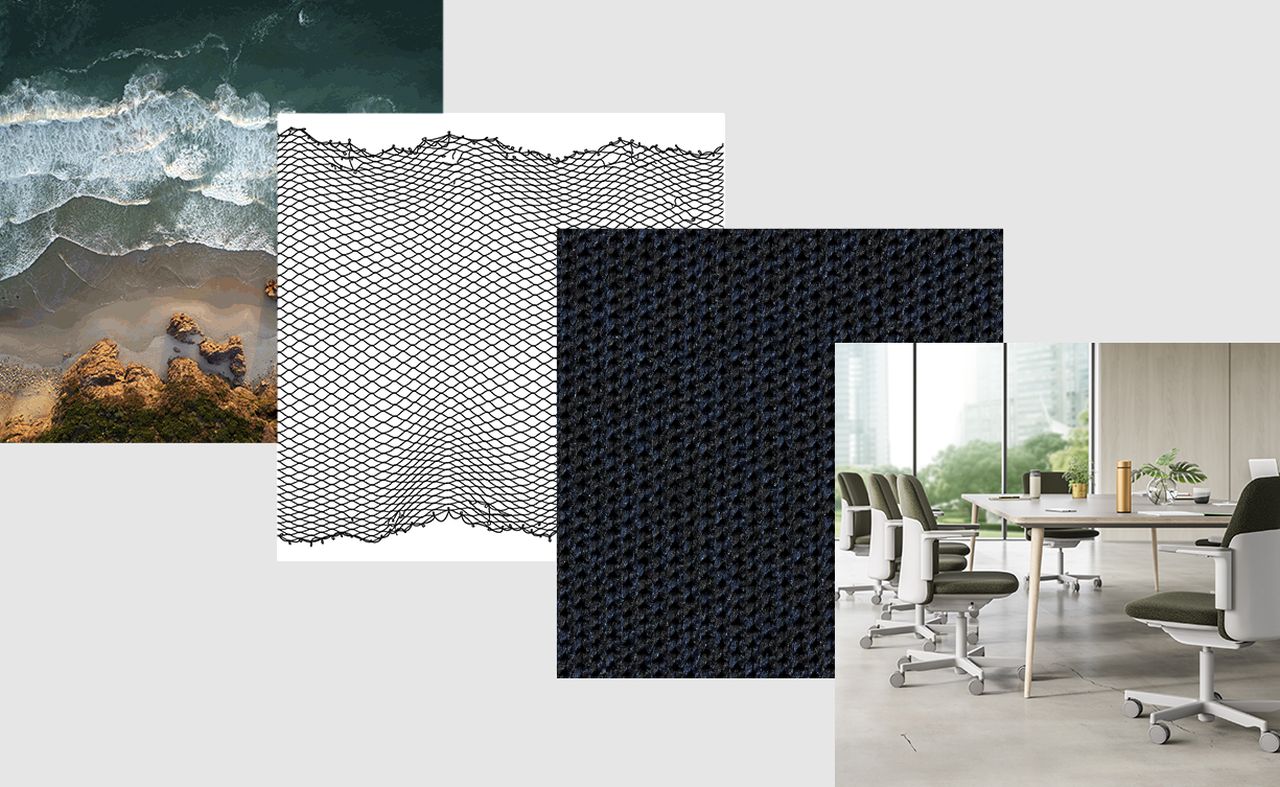

For the materials, I think there are probably two. We always have projects on the go to push the boundaries and see if there are new innovative materials and how they could be used. One of the big ones that we looked at – that we launched recently – was ocean plastic with a big focus on fishing nets.

They are the most harmful kind of ocean plastic and they’ll harm fish for decades, possibly hundreds of years. And it’s amazing how much plastic is flowing into the ocean every year. So our initial focus was on fishing nets, recapturing them and pulling them back out.

Quickly, you start to say there’s no reason to have the fishing community release the nets and then go back to get them. They start to bring them indirectly and trade for the new net. So we have systems in place to start to prevent material from going into the ocean as well.

I think it’s another version of circularity and it has been it. Getting people to think differently about the material. The material that’s flowing into the ocean is currently deemed waste and that’s not an inherent property of the material. That’s just our attitude towards it.

We decide that we don’t want to use that material as people. Human beings decide that they don’t want to use that material anymore and if we can change people’s minds and have them see value in that material, we can bring it back and have it flow back into the economy and start to be used again, as opposed to flowing into the oceans.

So that was one of the things we’re excited about. As you’re on that journey, we connected with NextWave (an organization keeping plastic out of oceans) and we’re a founding partner of NextWave initiative to start connecting different manufacturers. We’re trying to collect ocean plastic and use it in their products.

We’re all coming from different industries; some industries overlap, some do not, but there are a lot of different industries that represent a lot of different kinds of plastic and I think it’s an exciting project to be a part of, to see what’s possible. Instead of seeing this as a problem with that much plastic being out there, can we see it as a resource that we start to pull out and use? But more importantly, starting to prevent it from going into the ocean in the first place.

PC: What is the next big thing for Humanscale? Can we expect more innovative materials and projects from you?

JA: Yeah, I would expect so. We always have a lot on the go and a lot in the works. I would say that sustainability projects do take a fair bit of time so they can be years long in development. I don’t know which ones are going to come to fruition next, but we are always working to remove toxic ingredients. So this year we will have eliminated any antimicrobials added to the products.

We’ve been focusing category by category to remove ingredients that are hazardous to human health. We are also always looking at new and innovative material so we’ve been exploring that world a fair bit. With our design team, we have a lot of exploration happening in new materials that are coming out.

There is also the ocean plastic front, always looking for new suppliers, always working on different additions to different products, and working with NextWave. One of the focuses of NextWave is to try and get more manufacturers on board, using more material. So we’re trying to support their work at the same time.

So I can’t say which project we’re going to announce next. We did just – maybe a week or two ago – announce that we were certified by B Corp. For that, even though the audit process took over a year long, it was nice to be able to announce that came to fruition.

Image: Humanscale

PC: Humanscale got certified as a B Corporation. How significant is that recognition?

JA: Yeah, it was an exciting accomplishment for us. It aligns closely with our values. As I mentioned about 10 years ago, we thought can we manufacture, be a for-profit business, and be a force for good in the world? Have a net-positive impact when we measure all of our impacts in the world? Could the total amount have a positive impact?

The B Corp, B Lab, and the organization are focused on trying to have the business be a force for good. So philosophically, it aligned really closely. The audit process was quite extensive, which was good. It was also nice to see that a lot of the initiatives and the work that we had done over the past 10 years contributed to that recognition and we were able to just document what we had been doing and show, here’s what we’re up to, as opposed to having to make any internal changes. I don’t think there were any internal changes that we made, but it was more a process of really being thoroughly evaluated.

I think that it’s really interesting to see that there’s, as you mentioned, even the tension or there’s an assumption that you’re either interested in making a profit or you’re going to be sustainable. And they’re often pitted against each other. I think the more we can start to see that they’re not inherently misaligned. We can choose to see them as opposites and evaluate them against each other, but there are a lot of ways in which they support each other.

I think the more we start to transition our thought process into how business starts to be a force for sustainability, for good in the world, for environmental and social improvement, that will benefit all. There’s a lot of momentum behind business so it’s a really powerful force that we can align with sustainability and social impact.

PC: Can you tell me about a project that didn’t work out as expected? And what did you learn from that?

JA: My philosophy or my approach to work is one of tenacity and I usually say that my project hasn’t worked out yet. So that’s how I think about it. Nothing has worked out until it does. There’s always a challenge and challenges to overcome.

I’ll use the example of ocean plastic. One of our chairs where we tried this particular kind of plastic, we did many tests and many samples and we weren’t able to get it to work. We had several months of testing. Now we’ve got different components that we’re testing with and we’re actually making those components in-house so we were able to tweak some of the manufacturing differently and we’re now able to make those components from ocean plastic now where we couldn’t get our supplier to do it.

So that kind of comes full circle to things that are accomplished. But if you talked to me a year and a half or two years ago, I would have said that chair didn’t work out. And now, it hadn’t worked out yet. I would say we’re removing any harmful components; in the building industry, there are still a lot of ingredients that are carcinogens, mutagens, and reproductive toxins. So we’re voluntarily working hard to understand everything in our product and eliminate those.

We are very close to having eliminated all of them. There are still some projects in the works that have not been completed yet that are not yet successful. We’re pushing very hard on circularity, but what we’ve been doing is pilots to understand how to make that happen.

As we do the pilots, we learn the innumerable things that we didn’t know in trying to implement circularity. It’s really easy to talk about in theory and be excited about the idea of circularity. But when you go to put it into practice, you can’t possibly think of all the details that need to be addressed.

Image: Humanscale

So one by one, we’re going to it. We’re addressing them. I would say our pilot projects have been completed, but they were learning curves. I can’t say they’re successful or not successful because the intention was for us to learn, but they’re not like something ready to be launched immediately afterward.

That’s not come to fruition yet, either. We will be launching a circularity business model, probably in about a couple of months or so. We’re ready to launch that. There are many learnings along the way where there are different opportunities that I think we will also explore in the future.

On a regular basis, I deal with things not working out; and then I just kind of say, they haven’t worked out yet. We’re going to figure out the next steps

PC: People used to cherish the heirloom furniture. Now it’s all about fast fashion, modular things, and the idea of IKEA. Do you believe greener ways can change the furniture industry?

JA: Yeah, I do find that trend is happening. I think people almost go through a cycle where they go through one or two versions and then they’re like this is just not worth it.

For example, you might have a chair, you’re sitting in to do your work, that was very inexpensive and you’re like, I just need to sit down and work at a computer for a while. Then you pay for it by having back aches and neck aches, and you damage your body. I do find folks often sometimes start at that point and then realize that the upfront investment is small compared to the long-term investment of buying fast furniture and cycling it through.

Then you have to buy it again and again and again, and actually, it starts to add up and become more expensive. It comes down to the context of short-term thinking versus long-term thinking. People sometimes then realize that it’s worth investing a little bit more.

There’s fast fashion but of course, now there’s like slow fashion and the reaction to that and folks that are making like a 25-year T-shirt and products that are intended to last. They’re starting to become more of a market for folks who are willing to invest in that and want that.

They want to have the item that they love and cherish and continue to cherish for years. So I see there’s a lot of change in the way people are thinking. I do think that people are starting to shift back the other way and that the pendulum is maybe starting to shift the other way in at least a certain amount.

PC: What is your favorite material to work with as a designer or as a sustainability officer? What is that material that you find amazing?

JA: So I would rarely think about a material in isolation because as I mentioned, usually when I’m designing I would be thinking about the design challenge and what’s going to solve that challenge and everything in between.

Even aesthetics would be considered part of the design challenge because what’s beautiful to me and appeals to me might not be the target audience and I try to make them appealing to myself as well, but there could be differences if I’m aiming for an audience of pre-teens compared to somebody in a different phase of life, there will be difference in design aesthetic choices.

Instead of material, I’m going to mention a thought process that I like. That’s biomimicry. This is an idea that’s been around for a while and was very well described in the book Biomimicry.

It came out in the ‘90s; it’s a school of thought and the idea is that life has been around 3. 8 billion years and you can think about it as maybe iterating on some of the design challenges. If you want to think about how do I make something with really high tensile strength? Or how do I make something that’s impact-resistant? All of these are challenges that in an engineering world you might be looking at. In the natural world and the biological world that may have been solved in many different ways and iterated over millions and millions of years to refine it.

We have a lot of design solutions that are available to us if we’re willing to learn from nature and become students of nature and start to learn from what’s possible and even some of the systems thinking and the way that nature organizes itself. I think we can learn a little bit about how we set up our systems as well.

Image: Humanscale

PC: What is your favorite chair design?

JA: I sit in SmartOcean, so that was the first house chair with ocean plastic in it. It was exciting to have that chair come out and show that it was possible to use ocean plastic.

At first, we were trying to prove to ourselves internally that it was possible. We did find some others in the industry. We followed and started to use ocean plastic as well, which is awesome.

It fits many different types of backs, including mine. I have a very small back and it’s also really nice to be able to move freely. It supports you as you don’t have to stop and think about moving while knobs and levers support you when you lean back because you can just move spontaneously.

It lets me move a lot more throughout the day without even thinking about it, which is how it should be. So that’s my favorite chair.

Here is the video interview:

We thank Jane Abernethy for taking the time to converse with us and giving insights into the Humanscale sustainability initiative!