Conservation Talk with Anish Andheria, President of Wildlife Conservation Trust

In-depth perspective on human-wildlife conflicts and roadblocks to wildlife conservation in India

Dr. Anish Andheria, CEO of Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), India, needs no introduction. He is a well-learned man who is a renowned conservationist by profession and wildlife photographer by heart. A celebrated author and a regular columnist in India’s top newspaper publications, Anish and his organization work across more than 160 national parks and sanctuaries across 23 states of India.

Dr. Anish Andheria, CEO of Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), India, needs no introduction. He is a well-learned man who is a renowned conservationist by profession and wildlife photographer by heart. A celebrated author and a regular columnist in India’s top newspaper publications, Anish and his organization work across more than 160 national parks and sanctuaries across 23 states of India.

Planet Custodian gets into an exclusive chat with the President of WCT, where he sheds light on the man-wildlife conflict and conservation obstacles in the country. Anish also shares some of the notable highlights during his tenure and tells us he is not a big fan of the reintroduction of species. Read on to find out his views on these matters.

Planet Custodian (PC): Tell us a little about yourself.

Anish Andheria: I head the Wildlife Conservation Trust, and have been a conservationist for the last 25 years. My basic degree and Ph.D. are in fluid mechanics, but I also went on to do my master’s in Wildlife biology and conservation after completing my Ph.D. I’ve been heading Wildlife Conservation Trust since it started operating on the ground in 2009.

So it’s almost now more than 13 and a half years. We are about 85 people and we work across several Indian landscapes in more than 160 national parks and sanctuaries, in about 23 states.

PC: You’ve served as the President of Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) for more than a decade. What are some of the notable highlights?

Anish: Well, conservation is a long-term game. While there are many successes along the way, achievement is temporary, and failures are permanent. So, we have been able to catalyze by upgrading several forest areas to the level of a sanctuary. We have been able to give scientific input so that the government could expand the borders of several core tiger reserves. We have also been able to catalyze the declaration of buffer zones outsized server tiger reserves. So we have been able to influence some level of protection in almost 8,000 square kilometers of Central India.

That I would say is a sizable contribution when it comes to securing land for nature, for biodiversity. We pursued several projects on the ground to reduce human-wildlife conflict too. One of the most important ones (very close to my heart) is the water heater project where we have distributed (obviously not sole distributors) water heaters to the communities with a subsidy of 75%. This particular project is making life easier for women in these rural areas surrounded by forests and wildlife.

As a result, their visits to the forest to collect fuel wood have gone down by 30-35%, thereby, reducing the probability of interaction with large carnivores. So a lot of villages are willing to spend 1,850 rupees on this water heater. Even during the COVID pandemic, we saw no drop in the purchase of the water heater. Even with a collapse in the economy in such regions, people wanted the water heater as they felt far more secure with it.

There are several other things, the human-wildlife conflict work that’s been done by our veterinary doctors is fantastic. We have been able to rehabilitate several tigers in the wild. They captured them, put on a radio collar, and then released them and monitored them till they become used to the natural environment wherever they’ve been released.

The linear infrastructure projects where our researchers have gone in and collected a lot of data on animals that were crossing highways. And when these highways were expanded, which means the two-lane highways were expanded to four-lane and six-lane. Our research basically resulted in the government building underpasses on these highways. The government agreed to build these bridges so that vehicles can go on top while the wild animals can go below.

Image: Wildlife Conservation Trust

PC: Other than the human-wildlife conflict, what are the other major roadblocks to wildlife conservation in India? How can the common masses help preserve threatened species in their habitats?

Anish: There are several hurdles to conservation in India. Human-wildlife conflict is a result of conservation actually. The human-wildlife conflict was much lower in the 60s and the 70s because the wildlife population had collapsed.

But since 1972 and the declaration of the Wildlife Protection Act, all that was banned. Since then, the populations of herbivores like pigs, spotted deer, and sambar have gone up, and therefore, the large carnivore population has steadily gone up.

India has doubled the tiger numbers. There were 1,411 tigers in 2006, and by 2018 that population had reached almost 3000. Simultaneously elephant populations, rhinos, and lion populations had also gone up. So because of that the interface between large mammals and people went up and consequently, conflict incidences went up.

But I think species conservation is a byproduct of the conservation of ecosystems. For example, if you don’t have good-quality wetlands and rivers, you will not have dolphins. You will not have crocodiles, definitely, you’ll not have mahseer, which is an endangered fish in India. If you don’t have good quality deserts, then you will not have the wild ass or the desert fox. You’ll not have the species like the houbara bustard, which are found there. Similarly, if you don’t have good quality high-altitude mountains with enough prey base, you will not have snow leopards.

So securing land is very important and in India where you are looking at 1.4 billion people and the need for the nation to develop, means that the government is constantly trying to build roads. Developmental projects like dams, mines linear infrastructure like railways, roads, and electrical lines, are the main causes of the fragmentation of land.

When land fragments, animal populations get isolated with a lot of vulnerability and animal populations can go extinct because there is no immigration possible. If something goes wrong on one side, the population will collapse.

PC: Can we have some sort of equilibrium between conservation and development?

Anish: There is equilibrium in some places in India, in others, there isn’t. And this is a global thing. And there I think there is enough technology with us to ensure that conservation and development can go hand in hand. Some extra costs will have to be incurred, like mitigation structures on highways. So if a highway was built on the ground, it’ll be cheaper than an overpass. Similarly, if you have smaller dams, you will be able to allow reverse migration for fish because fish goes up for spawning.

Wild animals need to be protected for the forest to thrive as a healthy ecosystem. From a well-preserved forest, you will have better sequestration of carbon. You will have more pure water coming out of it. In a country with 1.4 billion people and where nearly 60% of these people are farmers, you can understand the importance of surface water, which means rivers have to keep flowing if these farmers have to cultivate.

There are challenges. One is the population, the second is the development and the third is the interface between wildlife and people. Because wildlife and people live in a very closely packed mosaic. The urban centers are right in the middle of the forest.

PC: AI is actually being used as a tool to enhance ecosystem mapping in various countries. Can you tell us what it is and how it works in wildlife conservation? And is it a viable solution for a country like India?

Anish: AI is used to identify tigers from a million tiger photographs. There is camera trapping, a methodology used to estimate tiger densities. The camera traps are put in different parts of the forest. One camera trap pair per two square kilometers and India has three and a half lakh square kilometers of tiger reserves. So really 1.75 lakh camera traps are put across the tiger habitats. Today AI is used to identify tiger photos from non-tiger photos. Leopard photos from tiger photos. Once that is done, then within the tiger photos they can truly identify individuals.

We feed data to AI which allows the system to improve. So every time that you feed data to the system, the system becomes more and more robust and can help predict conflict in the future. So if you put certain variables as to these are the reasons why conflict is happening, and if you run that in through on the computer and you feed data in other areas of the same landscape, the system will allow you to predict which are the most vulnerable hotspots for the future.

The best way to handle conflict is proactively and AI definitely helps in this. AI can also help in estimating populations of several animals like gharial crocodiles. Once you start feeding data to the system, then the system will help you in reducing the amount of effort that the team has to put in, which means that you can find solutions on time.

PC: WCT collaborates with indigenous people for wildlife conservation in India. How do they help in the preservation of the ecosystem?

Anish: Wildlife protection is definitely a success in areas where communities have contributed in a big way. The culture of the people living around Gujarat, where there are over 650 lions, is playing a big role. Even when a lion kills a cow or a buffalo, people don’t get angry, so wherever the wildlife population is high, the community is far more tolerant.

There are cases in Rajasthan where Bishnoi women have actually breastfed orphan antelope fawns. If the mother has died, lactating women in the village breastfeed the baby.

Tadoba is a tiger reserve in Maharashtra, where 604 villages are in the forest along with 75 to 80 tigers, both adults and cubs living together with people. Over the last two years, we have seen almost an average of 45 to 50 people have been killed. Over 5,000 cattle are being hunted by tigers in the landscape between Tadoba and Bramhapuri. It’s a huge amount of loss when it comes to cattle. However, people don’t poison tigers.

58,000 people in India die of snake bites every year. When there’s a snake inside a house in Bombay, I get a phone call to come to rescue it. Nobody says, there’s a snake in my house and I want to kill it. They’ll call and say there’s a snake, we have shut the door, come and take the snake away. So I think communities have a big role to play.

PC: India also suffers from a conservation bias by channeling disproportionate funds to saving magnificent mammals and avian species as compared to the rest of the species in the animal kingdom. What are your thoughts?

Anish: Yeah. So that happens across the planet, it’s not about India. Money is not easy to come by because when it comes to conservation, it’s really not making a profit for the government in a big way or for the corporate world. So by securing a tiger or securing a forest or securing a river, you don’t earn money overnight. It supports human populations for hundreds of years. But while that is very important, it is impossible for a human brain to make sense of it.

There is oxygen, there is water, and there are ecosystem services like pollination, germination, soil conservation, rivers, temperature regulation, and minor forest produce creation. These are all ecosystem services, but we cannot liquidate them. And so there is a concept that it’s a waste of money, resulting in a disproportionate amount of money that is going into non-forestry activities.

The corporate world wants to align with large mammals, powerful animals, with carnivores. Because if I was a capitalist and I was running a firm, I would want to associate it with an animal that is universally known as the most powerful animal. And so it’ll be either an elephant or it’ll be a whale or a shark or a tiger. It is also the perception that puts more money towards them.

But overall conservation receives one-10th of the money that it deserves. So if there is a lot of disproportionality there when it comes to supporting large members, I say there is nothing wrong with it.

If you are looking at tigers, they live in large areas. A female tiger will require 10 to 15 square kilometers of land, a male will require 50 square kilometers or as large as 200 to 250 square kilometers. So if I want to secure a tiger, I will have to protect a large area. And if I protect the large area, automatically, many insects, ants, termites, bats, butterflies, beetles, and plant species in that area will get secured.

If people want to support them because they are large-ranging marine mammals and mammals on earth, you are indirectly supporting everything else. I personally feel there is a bias for sure, but that bias is not really creating a lot of issues.

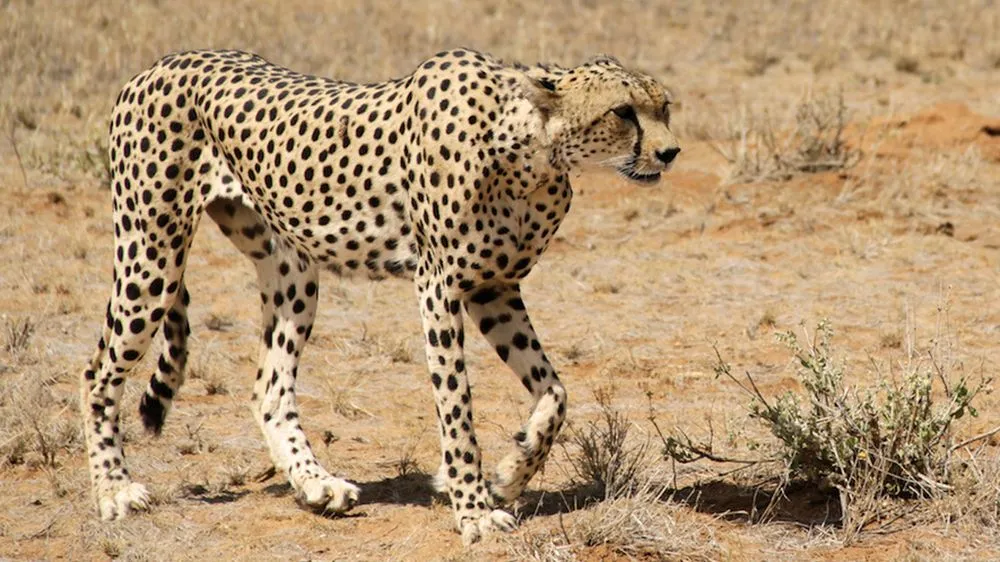

PC: What are your thoughts on this cheetah rehabilitation plan in India?

Anish: I think I’m not a big fan of the reintroduction of species because I feel that there are reasons why those species went extinct, and those reasons still exist in the country. However, now that the cheetah is here, I feel that we have to take advantage of the fact that the cheetah is iconic. The government can be advised and pushed to allocate good quality lands and grasslands for the species.

There are populations of cheetahs in Africa living in the woodland, but those densities are much lower. So if you want to back the cheetah project and ensure that there are about 150 cheetahs in the next 10 to 15 years, then you will need about 10,000 square kilometers of good-quality grasslands. India has lost nearly 200,000 square kilometers of grassland in the last 150 years. Cheetahs’ reintroduction could help restore the lost grasslands.

Image: 17QQ

PC: As a biologist and a wildlife photographer, which place did you find the most captivating? Moreover, what does it take to organize and manage such a big organization?

Anish: Teak forest mornings are beautiful. I love them, but I feel equally excited when I’m in a floodplain where there’s elephant grass. I love being in Ladakh, which is a trans area with not a single tree, but all those rugged mountains there. I love to be in a marshland. I love to be in the sea. I dive a lot.

I think the question can be better answered by saying that all those areas where human imprinting is minimal are my favorite. So going to the sea and finding no plastic in there and the biodiversity thriving, that’s something I love. There are so many different places on land as well. I love Kaziranga. I love Corbett.

Image: Anish Andheria

To answer the second part of your question, I don’t think it’s difficult if you know your goal if you know that you want to make sure that large landscapes have been secured. For any organization, the leader is playing only five to 10% of the role to make sure the staff feels secure that they can go out and follow their heart and not worry about funds. They are given the freedom to do what they want to do as long as they are going in that particular direction, which the organization has decided through a collective process.

We work collectively today with people from so many different sectors. We all come together and work as a think tank and most of our projects are complex. People look at it from different perspectives, and therefore the solutions that WCT comes out with are rounded because it takes into consideration not just what a conservation biologist or zoologist aspects, but also from the social and economic angle.

We thank Anish Andheria for taking out time to talk with us about human-wildlife conflicts in India and what roadblocks we face when it comes to wildlife conservation and what are the potential solutions.