Researchers Reveal Link Between Size of Ocean Plastic and its Consumption by Marine Animals

Plastic pollution has plagued the whole planet, earth and water alike. Thousands of tons of plastic end up in oceans every year and threatens the lives of marine species. We do know that ocean plastic affects aquatic animals, however, how deeply it affects them is still unclear. We don’t know a lot about where it ends up and what exactly it means for marine ecosystems.

The scientists at Cardiff University have come up with a way of predicting the size of the biggest pieces of plastics different animals can consume. They studied the stomach contents of thousands of animals to determine the risks posed by different types of plastic waste to marine species.

Cardiff University have come up with a way to determine the size of plastic marine animals can consume / Image: Bustle

While the effects of plastic waste on aquatic species are largely unknown, researchers are trying to unveil the details around why they consume it and its aftereffects.

For instance, a 2016 study uncovered that seabirds gobble up plastic because it smells much like dinner. A paper published earlier this month revealed that microplastics can cause aneurysms and reproductive changes in fish. Another recent study found out that marine animals including turtles and whales consume the plastic debris present in oceans because they smell like food.

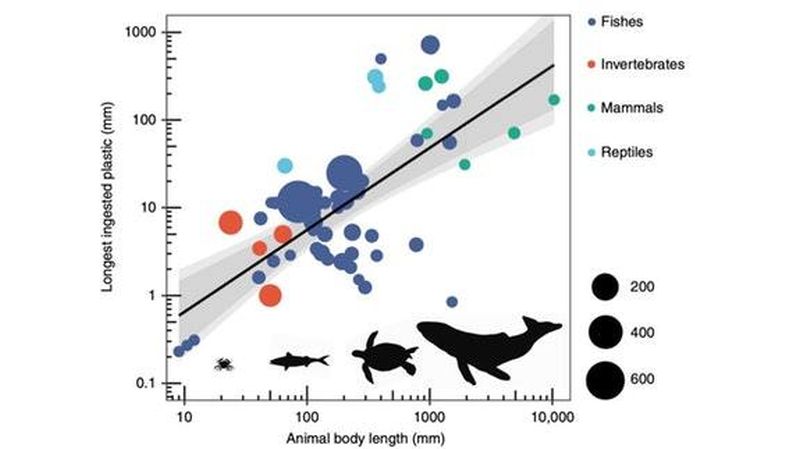

The new study at Cardiff University’s Water Research Institute has shed light on a few more details. Analyzing already existing data, the researchers examined the stomach contents of more than 2,000 mammals, reptiles, fish, and invertebrates, ranging from fish just 9 mm long to 10-meter-long humpback whales.

All of us will have seen distressing, often heart-breaking, images of animals affected by plastic, but a great many more interactions between animals and plastic are never witnessed. This study gives us a new way of visualizing those many, many unseen events. While we understand increasingly where concentrations of plastic in the world’s aquatic ecosystems are greatest, it’s only through work like this that we can know which animals are likely to be in danger from ingesting it.

Project leader Professor Isabelle Durance said.

The study shows that there is a direct relationship with their size and the largest pieces of plastic waste they could consume, which they calculated to be a ratio of around 20:1. The plastic samples studied include all kinds of materials, ranging from hosepipes in a sperm whale to plastic banana bags inside green turtles, but overall the largest pieces an animal could eat was around five percent of its size.

Cardiff University have come up with a way to determine the size of plastic marine animals can consume / Image: Cardiff University

The ingestion of plastics appears to be widespread throughout the animal kingdom with risks to individuals, ecosystems and human health. Despite growing information on the location, abundance and size distribution of plastics in the environment, it cannot be assumed that any given animal will ingest all sizes of plastic encountered.